In May 2018, I started working with Dr. Naomi Wright from the King’s College of London on the Global PaedSurg study on the management and outcomes of 7 GIT congenital anomalies in high-, middle-, and low-income countries.

Results of this study showed that survival for a baby born with a birth defect – otherwise known as a congenital anomaly – is dependent on where you are born, according to our team of scientists from 74 countries.

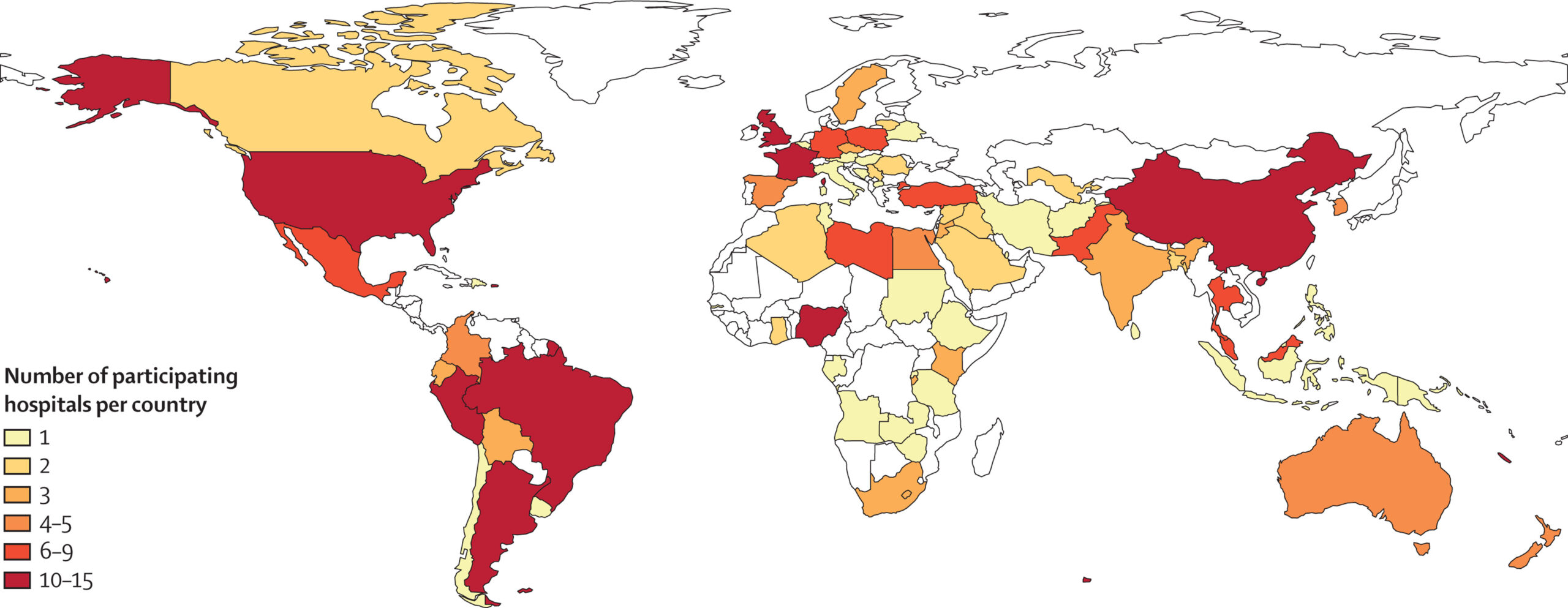

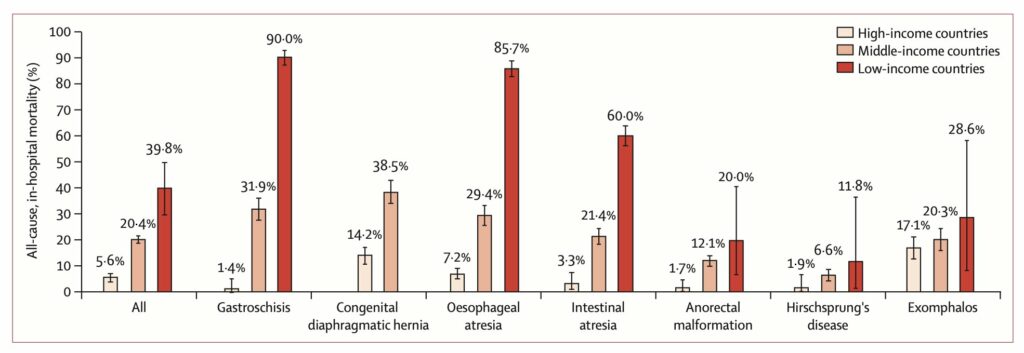

Our study published in The Lancet examined the risk of mortality for nearly 4000 babies born with birth defects in 264 hospitals around the world. The study found babies born with birth defects involving the intestinal tract have a two in five chance of dying in a low-income country compared to one in five in a middle-income country and one in twenty in a high-income country.

Gastroschisis, a birth defect where the baby is born with their intestines protruding through a hole by the umbilicus has the greatest difference in mortality with 90% of babies dying in low-income countries compared with 1% in high-income countries. In high-income countries, most of these babies will be able to live a full life without disability.

The below figure shows the all-cause in-hospital mortality for each congenital anomaly in by country income.

Principal Investigator Dr. Naomi Wright has devoted the last four years to studying these disparities in outcome. She said: “Geography should not determine outcomes for babies who have correctable surgical conditions. The Sustainable Development Goal to ‘end preventable deaths in newborns and children under 5 years old by 2030’ is unachievable without urgent action to improve surgical care for babies in low- and middle-income countries.”

The team stresses the need for a focus on improving surgical care for newborns in low- and middle-income countries globally. Over the last 25 years, while there has been a great success in reducing deaths in children under 5 years by preventing and treating infectious diseases, there has been little focus on improving surgical care for babies and children and indeed the proportion of deaths related to surgical diseases continues to rise.

Birth defects are now the 5th leading cause of death in children under 5 years of age globally, with most deaths occurring in the newborn period. Birth defects involving the intestinal tract have particularly high mortality in low- and middle-income countries as many are not compatible with life without emergency surgical care after birth.

In high-income countries, most women receive an antenatal ultrasound scan to assess for birth defects. If identified, this enables the woman to give birth in a hospital with children’s surgical care so the baby can receive help as soon as it is born. In low and middle-income countries, babies with these conditions often arrive late to the children’s surgical center in a poor clinical condition. The study shows that babies who present to the children’s surgical center already septic with infection have a higher chance of dying.

The study also highlights the importance of perioperative care (the care received on either side of the corrective operation or procedure) at the children’s surgical center. Babies treated at hospitals without access to ventilation and intravenous nutrition when needed had a higher chance of dying. Furthermore, not having skilled anesthetic support and not using a surgical safety checklist at the time of operation was associated with a higher chance of death.

We found that improving survival from these conditions in low- and middle-income countries involves three key elements:

- improving antenatal diagnosis and delivery at a hospital with children’s surgical care,

- improving surgical care for babies born in district hospitals, with safe and quick transfer to the children’s surgical centre,

- improved perioperative care for babies at the children’s surgical centre.

We acknowledge that this requires strong teamwork and planning between midwifery and obstetric teams, newborn and pediatric teams, and children’s surgical teams at the children’s surgical center, alongside outreach education and networking with referring hospitals.

We urge that alongside local initiatives, surgical care for newborns and children needs to be integrated into national and international child health policy and should no longer be neglected within global child health.

The article can be accessed, free of charge, in full on The Lancet website: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(21)00767-4/fulltext